Hip-Hop is Dead, Long Live Hip-Hop_

How did we get here_

For my first “official”, published project, I wanted to experiment with something completely different from the work I’ve typically done. Of course, I wasn’t sure what “quite different” would be until I saw a post on Twitter from someone shaking their fist at the clouds, claiming that “hip-hop isn’t what it used to be”, and that “old-school hip-hop was the true golden age of the genre.” Riled up by this comment, I started writing and rewriting a thorough reply—half constructively-critical, half vindictive. However, before I could hit reply and give Twitter’s engagement algorithm the satisfaction of (completely) gaming me, it hit me. My first project would set out to analyze how hip-hop has evolved, and perhaps come up with a more informed take on whether hip-hop’s supposed glory days are truly long gone.

This post serves as Part 1 of that journey.

*** [optional] click on right-side dropdown carets for additional detail

Where do we start_

Hip-hop is nothing without its rhymes, so we’re starting there. Unfortunately, there seems to be an apparent scarcity of existing literature focused on general rhyme detection. What does exist lacks the granularity and robustness to work reliably with something as linguistically dynamic as hip-hop.

Any debate about modern vs classic hip-hop inevitably focuses on lyricism. This makes sense, since at its most basic, hip-hop is spoken word poetry with a 4/4 time signature. Lyrics matter.

Generally, these debates center on content or technique: what is the artist saying, and how are they saying it. Part 1 of our exploration will focus on the latter. In particular, we’ll be building out the tools needed to identify rhymes, the foundational element of hip-hop technique.

Existing literature on rhyme detection is a mixed bag, best summarized by this blogpost from Johann-Mattis List, professor of computational linguistics (with an h-index of 40!).

In a nutshell, rhyme detection involves more than just identifying phonetic similarities between words. It also considers rhythm, stress, and creative language use, in order to accommodate unexpected and innovative rhymes that traditional rhyme dictionaries simply don’t account for. This is best represented by the kinds of slant-rhymes that you only notice when you say them out loud (ex. “dreams” <<>> “being”, or “platform” <<>> “clap for him”).

Existing papers have applied expectation maximization, Hidden Markov Models, and (foreshadowing) Siamese Recurrent Networks to identify structured rhyme schemes in traditional poetry, with some attention given to extracting structured rhyme schemes in more spontaneous rhyming styles from hip-hop. However, these analyses fall short for a few reasons. They only look at the line-to-line level. This leads them to fall short with hip-hop. Lines are labeled exclusively by end-rhymes, which means that they will omit internal rhymes and perhaps most glaringly, they also lack the flexibility to reliably detect not just slant-rhymes in General American English, but especially slant-rhymes according to hip-hop’s traditionally Black American dialects.

What’s the plan_

Here’s how I intend to build this rhyme-detector:

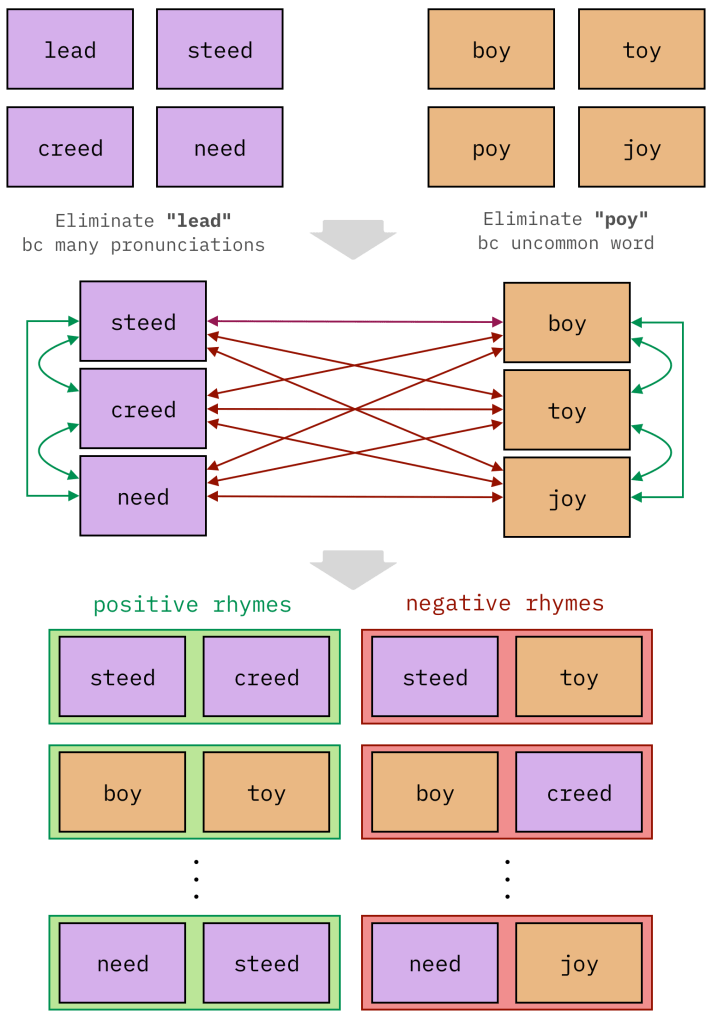

- Collect the data: Gather several thousand pairs of rhyming and non-rhyming words/phrases, which I’ve abbreviated to positive and negative rhymes respectively. Positive rhymes are labeled with a 1, otherwise 0.

- Preprocess inputs: Phonetically transcribe these English text strings using the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA), either with a pronunciation dictionary or semi-manually.

- Build the model: Train a Siamese Recurrent Network to take both texts as inputs, and output a similarity score between 0 and 1.

As with rhyme detection, it seems straightforward enough on first glance, though that would turn out to not be the case.

Some setup details_

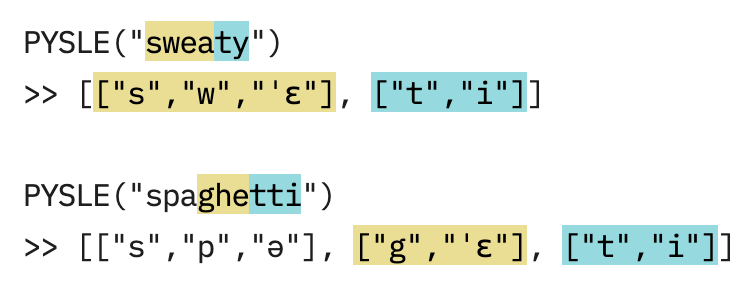

I’ll be transcribing English words into ‘IPA’, the metric system of phonetic-alphabets, aided by the python package ‘Pysle.’

PYSLE’s outputs

As mentioned in the plan-summary above, each word in my dataset needs to be phonetically transcribed. While there are a few phonetic “alphabets” to choose from, I chose the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA), as it’s more widely used and is capable of capturing more nuances in pronunciation.

However, I’m no linguist, so I can’t even begin to transcribe everything myself. Thankfully, there are pronunciation dictionaries integrated into various python packages, which instead of returning definitions, provide transcriptions directly. CMUDict in NLTK is a common choice, but I went with Pysle, as it is the only one that (1) uses IPA, (2) separates the transcription into syllables, and (3) separates each syllable into individual IPA symbols (phonemes).

Constructing the dataset_

In an effort to bootstrap a worthy baseline rhyme-dataset, I assembled rhymes from modern rhyme dictionaries like RhymeZone and RhymeWave. From an initial list of 20,000 words, I filtered out less common terms and those with dialectical variances, yielding 2,000 reference words. With the help of some combinatorial operations, I create a dataset of 250,000 labeled positive and negative rhymes (rhyming and non-rhyming respectively). Although the model performed well on the dataset (F1 – 0.97), it struggled with authentic hip-hop rhymes (F1 – 0.71), revealing the significant linguistic and stylistic gap between traditional datasets and the unique elements of hip-hop rhyming.

Visualizing automatic dataset generation

Our journey begins in earnest with the immediate realization that there are apparently no substantial, publicly-available rhyme datasets, which means that we’ll have to roll up our sleeves.

There are a few rhyme dictionary sites online, namely RhymeZone, RhymeWave, and B-Rhymes. Similar to a thesaurus site, you enter a word and receive a list of similar words, except these are ranked by rhyme-quality instead of semantic meaning. My plan was to come up with a list of input words, query the site with each word, and extract the resulting lists of rhyming words. My assumption was that the rules and boundaries of rhyme could be understood with any sufficiently broad dataset of rhyme pairs.

Starting from approximately 20k words, I filtered out uncommon words (based on Zipf-frequency), words with multiple dialectical pronunciations, and words that did not exist at all in Pysle. The result was a list of around 2k “reference words.” I could now iterate through this list, querying the rhyme dictionaries for each word, and then scrape the 50-100 unique rhymes. With positive-rhymes defined, I then focused on creating negative-rhymes. At a high level, I could take two reference words, gather their respective corresponding rhymes, and then create negative rhymes from the cartesian product of the two groups.

In the end, I had assembled a table of ~250k labeled examples of positive and negative rhymes…and it was largely for naught, as the data was mediocre. Regardless of the quantity of data or hyperparameter choice, the model excelled when validated against out-of-sample rhymes from the scraped dataset (F1~0.97), and disappointed when given realistic hip-hop rhymes (F1~0.71). Between the slang words, prefix/suffix truncation, unique contractions, and dialectical pronunciation, it became apparent that the gap between the dictionary datasets and realistic hip-hop rhymes was too large to bridge.

Constructing the dataset (for real)_

I finally opted to manually curate rhyme-pairs from ~30 modern hip-hop songs. I meticulously grouped positive rhymes by their intended rhyme sound, ensuring that all words within a group also rhymed with every other. For negative rhymes, I crafted a manual-labeling script that enabled me to hand-pick poor rhymes, ensuring they did not rhyme with any entry in the given positive group **under any reasonable pronunciation.** This work ultimately yielded a dataset of 8,000 rhyme pairs that better encapsulated the unique linguistic features of hip-hop.

Try as I might to avoid it, it was time to manually curate our dataset. If we had to roll up our sleeves before, we’ll have to cut them completely now.

Using the Genius API, I imported about 30 hip-hop songs from the past 5-10 years to ensure a reasonable mix of mainstream and innovative rhyming styles. For each song, I would carefully identify groups of words and phrases that rhymed together, focusing primarily on words that the artist “intended” to rhyme. At this point, my lovely girlfriend Greer had joined the effort.

I organized these positive rhymes into groups according to their dominant vowel sounds, ensuring that all phrases within a group could rhyme with each other. This approach would later allow for the generation of more rhyme pairs through combinatorial methods. To create the negative rhymes, I developed a labeling script that would display a positive rhyme group and then randomly suggest either: a) A string from a different rhyme group, or b) a random 1-5 word sequence from one of the 30 songs. Crucially, I made sure that this candidate negative rhyme did not rhyme with any phrase in the positive group under any reasonable dialectical pronunciation I could think of.

This method resulted in a dataset of over 8,000 rhyme pairs, each capturing the eccentric slang, truncations, unique contractions, and dialectical variations that thwarted the previous models.

Making phonetic transcription scalable_

Pysle alone is unable to provide all the transcriptions we need, so I built the `IPARetriever`. This class combines Pysle and Claude 3.5 Sonnet to dynamically select and save the right phonetic transcriptions for *any* phrase. It also perfectly replicates Pysle’s syllabified transcription outputs.

I should take a moment to discuss transcription and Pysle, as it presented a major obstacle to building a diverse dataset. Pysle has two main shortcomings:

- Its dictionary is fairly limited and sanitized, likely due to the fact that every entry needs an IPA transcription.

- Many entries have multiple IPA transcriptions, which makes said entry useless for unsupervised transcription as these judgement calls require a human-in-the-loop to select the correct one depending on the context. This is an inevitable but tolerable inconvenience when the pronunciations are functionally distinct (ex. “Follow my lead” vs. “lead pipe”), but many instances feature multiple phonetically redundant or purely dialectical transcriptions.

If I wanted to even attempt to capture hip-hop in a dataset, I needed a system that was robust to all of its linguistic quirks. To meet this need, I put together the IPARetriever.

This group of classes combines Pysle with Claude 3.5 Sonnet, Pydantic, and a local caching system to dynamically return the right pronunciations for any input phrase. The final outputs perfectly replicate the structure of Pysle’s transcriptions, syllables and all.

Motivating the choice of network architecture_

Based on previous works, we’ve landed on using a Siamese Bidirectional LSTM (biLSTM), an enhanced type of Recurrent Neural Network (RNN). Let’s say an RNN, an LSTM, and a biLSTM were college students. The RNN would take their lecture notes with disappearing ink, the LSTM would take their notes in pencil (not pen), and the biLSTM would print+read the lecture notes ahead of class, and then take notes in pencil during class.

With a dataset compiled, I could now work on building the model.

Building from previous works, I knew that a Siamese Recurrent Network (SRN) would be the go-to, specifically a Siamese Bidirectional LSTM (biLSTM).

At a high-level, an LSTM is an RNN with additional components that help capture long-term dependencies in sequence data, as opposed to primarily focusing on more recent elements. LSTMs achieve this through gating mechanisms that allow them to selectively remember or forget information, making them more adept at capturing relevant long-term patterns. Taken a step further, we can use two LSTM layers, one for each direction, to create a biLSTM. BiLSTMs are even better at capturing information from the entire sequence by processing it in both forward and backward directions, allowing them to consider both preceding and following context for each element. Finally, we can adopt a Siamese structure in order to accept two separate inputs, process them through the same network (ensuring they’re in the same ‘feature space’), and then evaluate how similar the two inputs are.

Let’s look at an example set of rhymes to see how these advantages can play out.

“eminent” <<>> “adrenaline”

“stimulant” <<>> “adrenaline”

“absolutely, they’re eminent” <<>> “adrenaline”

“evidently, they’re eminent” <<>> “adrenaline”

Both “stimulant” and “eminent” are good candidate rhymes for “adrenaline,” but the latter is superior because “emin-“ rhymes more closely with “adrenal-“ than “stimul-“ does. However, due to its recency bias, an RNN would have a tougher time (1) emphasizing this distinction given that it exists at the beginning, and (2) learning to not over-penalize the mismatched endings “-nt” vs “-ne”.

Say instead, we were given “absolutely, they’re eminent” and “evidently, they’re eminent” as candidates rhymes for “adrenaline.” While the latter is a better rhyme, the increased sequence lengths means is an obstacle for the RNN. The network will find it more challenging to preserve all of that information, and will not only evaluate these similarly, but will also likely ‘score’ them lower or more imprecisely than they otherwise should be. LSTMs, on the other hand, will not only be better at preserving the information most important for evaluating each rhyme independently, it will also be better at determining that they are different. This is due to their ability to selectively retain relevant information over longer sequences.

A bidirectional LSTM will be even more capable of preserving the most relevant information and demonstrating the relative difference in rhyme quality. By processing the sequence in both directions, it can better weigh the similarity of “evidently” to “adrenaline” using the right-to-left LSTM while still considering the strong end-rhyme using the left-to-right LSTM, resulting in a more nuanced and accurate assessment of rhyme quality.

Motivating the choice of loss function_

After designing our Siamese Bidirectional LSTM architecture, we chose Contrastive Loss for training, a method ideal for teaching our model to distinguish between rhyming and non-rhyming pairs. By comparing output vectors from the BiLSTM for each word pair, this loss function ensures rhyming words have similar vectors, while non-rhyming words are sufficiently distant in the model’s conceptual space. This approach helps the model grasp varying degrees of rhyme and generalize the concept of rhyming, enhancing its ability to detect rhymes across different contexts.

After designing our Siamese Bidirectional LSTM architecture, the next crucial step was to determine how to train the model effectively. This is where Contrastive Loss comes into play, serving as an ideal loss function for our rhyme detection task.

At its core, Contrastive Loss is about teaching the model to recognize similarities and differences. Imagine you’re teaching a child to recognize rhymes. You might say, “Cat and hat rhyme, but cat and dog don’t.” You’re essentially creating a mental space where “cat” and “hat” are close together, while “cat” and “dog” are far apart. This is exactly what Contrastive Loss does, but in a high-dimensional space created by our neural network.

Here’s how it works in our rhyme detection context:

- For each pair of inputs (like “eminent” and “adrenaline”), our Siamese network produces two output vectors.

- We calculate how similar these vectors are, typically using cosine similarity.

- If the inputs rhyme, we want their vectors to be very similar (close together in our high-dimensional space).

- If they don’t rhyme, we want their vectors to be different (far apart in our space).

The Contrastive Loss function encapsulates this idea mathematically. It penalizes the model in two ways:

- If rhyming words are not similar enough, it encourages the model to make them more similar.

- If non-rhyming words are too similar, it pushes them apart, but only up to a certain margin (don’t need “cat” and “dog” to be infinitely far apart, just far enough to be clearly distinguished).

Let’s consider an example:

positive rhyme: “fire” <<>> “higher”

negative rhyme: “fire” <<>> “water”

When training on “fire” and “higher”, the Contrastive Loss will encourage the model to produce very similar vectors for these words. But when it sees “fire” and “water”, it will push the vectors apart, teaching the model that these sounds are not similar in the context of rhyming.

This approach has several advantages:

- It can handle various degrees of rhyme, from perfect rhymes to slant rhymes, by allowing varying degrees of similarity.

- By learning a general notion of “rhyme-similarity”, the model can potentially recognize rhymes it hasn’t seen during training.

- It simultaneously learns what makes words rhyme and what makes them different, providing a well-rounded understanding of phonetic similarities.

By using Contrastive Loss, we’re not just telling our model “these words rhyme”, but we’re teaching it to understand the concept of rhyming itself. This allows our model to develop a nuanced understanding of phonetic similarities, making it capable of detecting various types of rhymes across different contexts.

The results_

After 23 epochs, our rhyme detector achieved a validation F1-score of 0.97 on a semi-holdout dataset and 0.85 on a complete-holdout dataset. The model effectively validated our earlier hypotheses about underlying-drivers of rhyme quality. Perhaps the most notable finding was the model’s apparent ability to recognize *paragoge*, which unlocks new slant rhymes by allowing phonetic additions, (ex, “quilt” <<>> “camilla”, where the “t” in “quilt” has a voiced sound “tuh”). These results underline the value of a manually curated dataset in teaching nuanced linguistic features.

After 23 epochs of training, our SiameseRhymeDetector managed a validation-F1 of 0.97 on a semi-holdout dataset (some training phrases appear in validation, but paired with a new rhyme phrase). However, on a full-holdout dataset (completely new words and phrases), it managed a validation-F1 of 0.85.

Let’s revisit our examples from earlier. The primary takeaway here is that the model completely validates our hypotheses earlier about which rhymes seem “better” than others:

Even for single-word rhymes, not all rhymes are created equal

“adrenaline” <<>> “eminent” – 0.881

“adrenaline” <<>> “stimulant” – 0.770

Rhyme quality is a function of the phonetic similarity across the entire input, not just the ending sounds

“adrenaline” <<>> “evidently eminent” – 0.868

“adrenaline” <<>> “absolutely eminent” – 0.646

“adrenaline” <<>> “evidently they’re eminent” – 0.642

“adrenaline” <<>> “absolutely they’re eminent” – 0.525

Rhyme quality is order-sensitive

“adrenaline” <<>> “absolutely eminent” – 0.646

“adrenaline” <<>> “eminent evidently” – 0.287

Here are some other rhymes that failed dramatically with earlier iterations of the model:

“dreams” <<>> “being” – 0.994

“clap for him” <<>> “platform” – 0.707

“marriage” <<>> “parents” – 0.650

“quilt” <<>> “camilla” – 0.855

That final example shows off the most interesting ability the model has picked up on, which is the ability to recognize potential examples of paragoge, defined as “the addition of sounds to the end of a word.” Personally, I’m most familiar with paragoge as employed by children whenever they’re whining particularly emphatically. For example, instead of yelling “stop” or “ew” or “no,” they may say “stop-uh”, “ew-uh”, or “no-uh.” However, this is also sometimes employed in hip-hop to help bridge a phonetic gap between two slanted rhymes.

“quilt” and “camilla” don’t seem like a good rhyme on the surface, but the model allows space for the inclusion of a paragogic vowel (“quilt” —> “quilt-uh”) which makes “quilt” a very strong slant rhyme for “camilla.”

Instances like these are the best justification for manually curated datasets, as any other method of creating rhyme-data would not have generated such examples to teach the model that rules of rhyming can be bent in such a way.

In the next part, I’ll explore how I might use this rhyme-detector as a tool to identify rhyme-groups.